Esotericism has something to with religion, with the supernatural, with the occult, with magic, and even with science. But what exactly is it?

This is the first of two posts looking at this topic. This one looks at six prominent views of what “esoteric” is about. It notes problems with all of these views. But, with one exception, they all add useful pieces that could be put into a more complex picture. The second post develops that picture.

Disclosure: I am a professor of religious studies who studies esoteric and spirit-incorporation traditions in Brazil (along with theory and methodology), and who has taught a university course on “Esotericism, Magic and the Occult” for many years. I am not a practitioner.

Defining “definition”

The first step to defining “esotericism” or any other complex idea is to start by defining “definition.” Otherwise, you often up talking past people who are trying to do different things. This way, you can start by knowing if you are on the same page or not.

One approach to definition is to start by assuming that words always point to things that exist “out there” in the world. This sort of real definition aims at a complete list of characteristics shared by all possible examples of the thing. Definitions of this kind are true or false: you either draw the right line around the thing, or you don’t. (And that is how fights get started about the one, true definition.) This approach usually works well enough for things you can see and get your hands on. But it is not a promising start for defining abstract ideas like “religion,” “justice,” “culture,” “ideology,” “tradition,” “esotericism” etc. How do you list the defining characteristics of an abstract idea, when you are still trying to get clear on what it is?

A better approach for complex terms is lexical definition: defining words, not things. It aims not to defend some view of how the word should be used (because it’s “real”), but to describe how it has been used. Then you can choose between accepted views (or make up a new one and see if you can convert anyone). Definitions of this kind are not true or false (in the sense of capturing the “reality” of the thing itself). They are more or less useful for particular purposes. And they are open-ended: we revise our definitions as we learn more, and as usage shifts.

These two posts flag a path in a messy landscape of conflicting meanings. If you end up with a clearer idea of esotericism, then my view is relatively true ( = helpful) in this pragmatic sense.

Six views of esotericism

Here are six prominent views of what makes esotericism esoteric. (Bold and italicized font highlights a growing list of characteristics.) These are views that have been flagged or developed by scholars and specialists. (Wouter Hanegraaff offers an excellent, more detailed overview here.) The path to a lexical definition starts with how a particular group of people uses the word. Different groups come into play here: including both insiders and scholars.

1. Secret universal religious/spiritual Truth

Some esoter(ic)ists and scholars hold that all true religions, spiritualities and esoteric traditions are windows on the same sacred reality, once you get past their exoteric (surface) meanings to their esoteric depths. This itself is an esoteric or religious view. It is not a useful definition, because it asserts something that cannot be proven one way or the other. You can have faith in this view, or not. Either way, it has no value for defining esotericism in general. It is a nudge and a wink to the inside few: either you are already tapped into this one, true, core tradition, or you don’t really get it. This view might in fact be the truth, but it is not useful for the comparative study of esoteric traditions.

2. Secret knowledge

The origin of “esoteric” is an ancient Greek word for “inner” things. It was used to describe the secret teachings of Pythagoras. The Oxford English Dictionary defines “esoter(ic)ism” as “the holding of esoteric doctrines…” and “esoteric” as “designed for, or appropriate to, an inner circle of advanced or privileged disciples.”

For example, the image below is the Monas Hieroglyphica (the “One sacred sign”), from a 1564 book of the same name by scientist, magician and esotericist John Dee. (In esoteric circles, Dee is most famous for receiving, from angels, the Enochian magical alphabet, which is still used by practitioners of magic.) Dee believed that this symbol contained, in condensed form, a massive amount of knowledge on astrology/astronomy, alchemy/chemistry, theology, Kabbalah, mathematics, linguistics, music, optics, magic, and other topics. His book explains it all – if you can only figure out how to penetrate the obscure barrage of associations. The book is esoteric in subject matter (Kabbalah, alchemy, astrology, magic etc.), but it is also esoteric in this first sense of secret knowledge, written for the select few who have the knowledge to decipher it: “I give not only the principles but the demonstration to those who can see … certain that it is not mythical dogma but mystic and secret…. Here the vulgar eye will see nothing but Obscurity and will despair considerably.”

Until the past couple of hundred years, it was very common for writers of all sorts to present their ideas at two levels: a public level that most readers never get past; and an “esoteric” level, accessible only to those who read carefully and repeatedly. Two of my favourite authors – Sir Thomas Browne and Jorge Luis Borges – wrote esoterically in this sense. Both also used themes from European esoteric traditions: check out the last chapter from Browne’s most esoteric (in several senses) book, The Garden of Cyrus; and Borges’ most esoteric (in several senses) story “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” (pdf of an English translation here).

This characteristic is only a partial fit as a definition. It includes too much: esotericism, in this hidden-meanings sense, was long found in many types of writing, not just in esoteric traditions. And it leaves out much: a two-level approach to writing and reading is only found in some esoteric traditions. This hidden-levels-of-meaning idea is useful – picking up on “occult” – but it can be at most one element on a list of characteristics of esotericism.

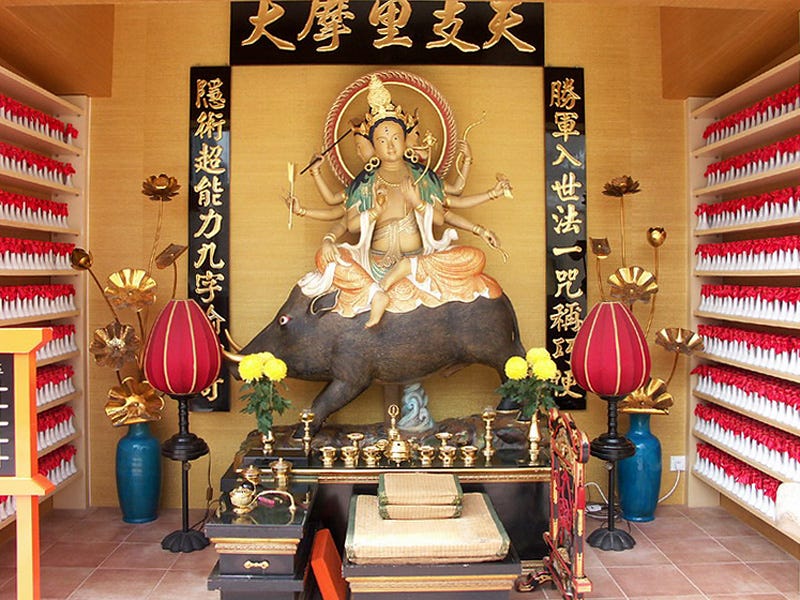

3. Esoteric (Tantric) Buddhism

This is a tendency within Mahayana (east Asian) and Vajrayana (Tibetan) Buddhism that emphasizes a cluster of things: for example, secret teachings; liberation of the body here in this world (sometimes by breaking ethical boundaries and using negative emotions); the Buddhist idea of skillful means (the ability of enlightened teachers’ skill at framing messages for specific audiences); complex rituals; and the multiplication of supernatural figures (Buddhas and deities, all portrayed in complex imagery). Some of these things are like some aspects of other esoteric traditions – but not all. We continue adding to a list of partial characteristics.

4. Six characteristics of Western Esotericism

The most often used definition of esotericism is Antoine Faivre’s list of six key characteristics of western (primarily European) esotericism. The first four are “absolute” and the last two (more common since the 1600s) are “relative”:

1. “universal correspondence … non-‘causal’ matches between all the levels of reality in the universe … relationships between the (macrocosm) and humanity (microcosm) …” (The Hermetic motto for correspondence was “As above, so below,” which holds that humans and this world contain imperfect (but perfectible) resonances of the divine. It is a fractal or holographic view of reality, with a divine original image, and everything else reflecting, in more distant echoes, that original.)

2. “Living Nature … [T]he whole of Nature, considered as a living organism … has a history, linked to that of humanity and the divine world” (This characteristic is not as common across the history of esotericism as in the period that Faivre was most interested in.)

3. “mediation and imagination … [R]ituals, symbols …, intermediary spirits, etc. … present themselves as so many mediations likely to ensure passages between the various levels of reality… [T]he ‘active’ imagination … exercised on those mediations, makes them a tool for knowledge …” (Faivre mixes three things in one here: levels of reality; entities at higher levels who help us move up; and the separate view that imagination is the human quality that allows us to pursue a spiritual path, like a divine compass inside us that smells out true teachings and allows us to find our way home to the One, the Creator, the pleroma etc.)

4. “The experience of … the transmutation of oneself …, and, as a corollary, of part of Nature (in many alchemical texts, for example)” (This is linked to the idea of mediation: the esoteric path involves your transforming through a series of higher selves, at higher levels of reality, on your way back to the divine. The ritual transmutations associated with progress through the [often] 33 degrees of esoteric Freemasonry is a good example.)

5. “concordance: common denominators between several different [esoteric] traditions are assumed [as a matter of principle]” (This points to the idea that all true traditions are aspects of the same spiritual path, the first of the six views (not this list of Faivre’s characteristics) discussed above.)

6. “the importance of ‘channels of transmission’; for example, master to disciple, from initiator to initiate”. (This is central to the common esoteric idea that all true traditions are passed down from authentic sources far in the past.)

Faivre saw these characteristics as the family “air” of a “form of thought.” Few types of western esotericism have all six characteristics, but most have some. (This is like a “family resemblance” approach to definition, which I will discuss in the next post.)

Not surprisingly, as with esoteric Buddhism, any list of characteristics depends on the model you start with. Faivre was a specialist in Renaissance Hermetism, Christian Kabbalah, and Christian Theosophy. His definition works well with them, but not so much with others, for example, nineteenth-century New Thought. Once again, we add to our list of characteristics.

5. Rejected knowledge

Wouter Hanegraaff makes a case that esoteric traditions are belief systems that were rejected by both religion (faith) and science (reason), as these two squared off against each other over the last centuries. The rise of Protestantism was a central factor, with its Bible-centred view of Christianity and its rejection of “superstitious” elements of Catholicism. Esoteric traditions had formerly been an essential part of the European intellectual landscape. Before the 1500s, you could not be a well-educated person without studying these traditions alongside philosophy, theology, rhetoric, music theory etc. This changed, for example, as astronomy and chemistry become sciences, while astrology and alchemy became pseudo-sciences; and as systematic and practical theology became central to religion, while magic and talking to angels and spirits became heretical or demonic. The “rejected knowledge” perspective is crucial for understanding the history of esotericism, but it is not that helpful for defining it. It clarifies the academic category of “esotericism” more than esoteric traditions themselves. Many things have been rejected by religion and science (in relevant senses) that are not esoteric, from “pagan” philosophy and Latter-Day-Saint theology to ether theory and cold fusion. The core issue is not rejection in itself but the historical shift from mainstream to marginal. But if we ask why certain European traditions were rejected at a certain point in history, we are still left looking for a list of “esoteric” characteristics that can describe what was rejected. After all, the many types of esotericism do have further things in common. (The problem is that we are left with a messy list of characteristics. But the follow-up post makes a case that this is not so bad.) If we let go of the idea that there must be some final winner-takes-all definition, left standing after the intellectual dust clears, then we can learn valuable things from all these six approaches (granted that the first has little value for comparative purposes).

6. Claims of higher knowledge

Kocku von Stuckrad begins with the view that differences between “religions” (Christianity, Judaism, Islam etc.) matter less than similarities (“discursive transfers”) that cross these and other boundaries. This leaves open the question of what makes the esoteric discursive formation different from others. Stuckrad calls his approach a “framework for analysis,” not a definition. This is helpful, but it leaves open questions. The idea of discursive transfer offers a framework that can guide scholars, but it does not provide criteria for distinguishing one discursive formation from another. That requires a list of characteristics. Stuckrad gives one, and that part of his argument is not a framework for analysis: it is a definition. Stuckrad points to several things: “the claim to a wisdom that is superior to other interpretations of cosmos and history”; individual experience; ontological monism (“unity of material and non-material realms of reality”); and “ascension to higher dimensions of reality” (a link between Faivre’s ideas of mediation and transmutation, something only implicit there). He also adds two that we have already seen: secrecy, and mediation (gaining spiritual knowledge through contact with “gods or goddesses, angels, intermediate beings or other superior entities”). Once again, we have added to our list.

Where do we go from here?

Each of these six views of esotericism and the esoteric is partial. But, as a group, they have generated a list of twenty characteristics (unpacking some of the above):

hidden-meanings

an inner circle of disciples

breaking ethical boundaries and using negative emotions

framing messages for specific audiences

complex rituals

multiplication of supernatural figures

correspondence between all things

living nature

a series of hierarchical levels of reality

higher levels entities that help us ascend

imagination as the human quality that allows us to follow truth

transmutation of the human self

transmutation of aspects of the world

profound overlap between esoteric traditions and ideas

historical and spiritual transmission

the rejection of esoteric traditions, as lines between religion and science sharpened in the last few hundred years

claim to superior wisdom

individual experience

unity of material and non-material aspects of reality

ascension to higher dimensions of reality

The next step is to wrestle with this list, adding to it, dividing it into sub-lists and generally looking for patterns. The partial nature of the six views discussed in this post suggest that we are not going to find some core, essential characteristic lurking behind this list. So, we will need to think about types of definition that work with lists. The follow-up post takes up this challenge.

Further Reading

Publications and on-line resources, beyond the links embedded in the text above:

There are many on-line archives of historical esoteric texts, for example Internet Sacred Texts Archive and Forgotten Books. The Digital Occult Library is also a solid resource, with lots of information and some links to texts.

Global Grey e-books is a great site with free, well-designed, multi-format, public domain e-books on many topics. It has a large and growing set of esoteric authors. Highly recommended.

For an excellent short overview of views about “esotericism” and its study, see Western Esotericism: A Guide for the Perplexed, by Wouter J. Hanegraaff. It is not a history or overview of esoteric currents themselves. Here is a useful shorter text (“Some Remarks on the Study of Western Esotericism”) by Hanegraaff.

The best overviews of the history of European esotericism are Western Esotericism: A Brief History of Secret Knowledge, by Kocku von Stuckrad (Google books gets the author wrong!) and The Western Esoteric Traditions: A Historical Introduction, by Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke. Others are not recommended (unless you can read the French original of Antoine Faivre’s L'ésotérisme, an excellent short introduction, though stronger on the period he was most interested in).

The best encyclopedic overview of European esotericism is the hefty, expensive, and increasingly hard-to-find, Dictionary of Gnosis & Western Esotericism, edited by Wouter J. Hanegraaff, with Antoine Faivre, Roelof van den Broek and Jean-Pierre Brach. Many university libraries have on-line access.

A valuable Dictionary of Contemporary Esotericism, edited by Egil Asprem, is in preparation. Pre-prints of several chapters are available here.

I don’t need to tell you that Wikipedia is a minefield – sometimes excellent, but often shot through with misinformation, partisan editing, insider distortions, and gaps in coverage – but the article on Western esotericism is a good resource, overlapping to an extent with this discussion.