This post looks at Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt’s 2017 book, The Coddling of the American Mind (CAM). Their book has a carefully delimited viewpoint. It largely ignores structural (social and economic) issues. This silence raises questions. Is there perhaps a different cause for the malaise that they and others diagnose: a new fragmentation of the individual subject, a separation of monetizable curds from useless whey within the American – and global – mind?

Trouble on campus?

Something unusual is going on at my university. Most (not all) of the young people I work with in my classrooms face challenges that students a decade ago did not. Most seem less prepared and less capable. They are more afraid of speaking-up in the classroom, less motivated and engaged, more likely to skip classes, more distracted by screens, less likely to ask for help, more anxious about grades (or totally unconcerned), less willing to participate in group work, more prone to procrastination, less comfortable with open-ended questions, more dependent on step-by-step instructions. They are less able to read and analyze longer texts, to take effective notes, to write focused sentences and clear paragraphs, to work with abstract ideas, to retain information, to distinguish credible from unreliable information, to articulate arguments orally, to manage time effectively, and to revise their own work.

What is causing this? Changes in elementary and secondary education? Cellphones and social media? Enforced lockdown and social isolation? Fears about future economic and climate prospects? Helicopter parenting and reduced independence? Erosion of attention spans from streaming culture? A cultural shift toward instant gratification?

The evidence supports my impression that something is up.

Jean Twenge’s 2017 study of survey data on 11 million young people, supplemented with in-depth interviews, leads her to conclude:

Born after 1995, iGen is the first generation to spend their entire adolescence in the age of the smartphone … perhaps why they are experiencing unprecedented levels of anxiety, depression, and loneliness. … They are also different in how they spend their time, how they behave, and in their attitudes toward religion, sexuality, and politics. They socialize in completely new ways, reject once sacred social taboos, and want different things from their lives and careers. More than previous generations, they are obsessed with safety … [and are] growing up more slowly than previous generations….

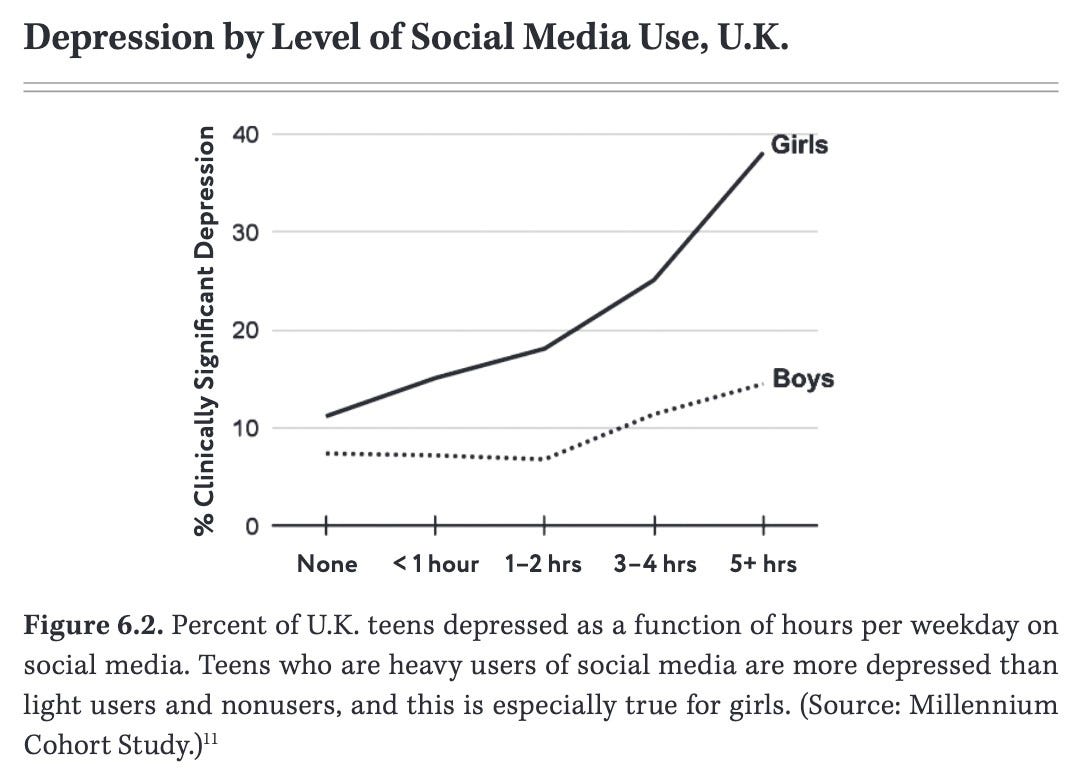

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s 2024 book, The Anxious Generation, draws on a wide range of data to argue that an “epidemic of teen mental illness … [has] hit many countries at the same time.” He discusses “more than a dozen mechanisms by which this ‘great rewiring of childhood’ has interfered with children’s social and neurological development”: including sleep deprivation, fragmentation of attention, reduced free play, addiction to social media and other apps, loneliness, social comparison, perfectionism, and the decline of ritual and spirituality. The evidence suggests that “social media damages girls more than boys and … boys have been withdrawing from the real world into the virtual world, with disastrous consequences for themselves, their families, and their societies.”

For a short, sharp overview, see Ted Goia’s recent substack post: What's Happening to Students?

New Thought and cognitive self-help

In CAM, Lukianoff and Haidt make a case that “good intentions and bad ideas are setting up a generation for failure.” They suggest that over-protection is undermining young people’s psychological development. Three “Great Untruths” now dominate campus culture: what doesn't kill you makes you weaker; always trust your feelings; and life is a battle between good and evil people. The book associates these beliefs with trends like trigger warnings, safe spaces, speaker disinvitations, political polarization, increasing anxiety, the decline of play, and an overemphasis on children’s safety in parenting and university administration.

I have talked to people who see the book as a critique of progressive values, as part of a biased discourse that led to the election of Donald Trump. That is wrong. Lukianoff and Haidt go out of their way to point out that they have never voted for a Republican. The word “woke” – a buzzword of anti-progressive views – does not appear once in the book. They note that “extremists have proliferated on the far right and the far left.” They point to increasing polarization between “the moral cultures of the political left and the political right,” with “provocations” from both. They note that “the right is just as committed to identity politics as the left.”

CAM works on an axis that is at right-angles to the left-right spectrum. It gives a diagnosis: fragility and lack of resilience are caused by overprotection and safetyism. Then it gives a prescription for this ailment: cognitive behavioural therapy can teach individuals to fix distorted thinking and build mental toughness. Fragility is the disease and healthier thinking is the cure.

The nature of this other spectrum is obvious from the word “mind” in the book’s title. The other key title word was originally “disempowerment,” not “coddling,” which the publisher rightly thought would sell. Cognitive behavioural therapy embodies an individualistic view of empowerment: it is a more empirically grounded cousin of self-help. The self-help movement, in turn, has roots in New Thought, an esoteric tradition that emerged in the USA in the late 1800s. New Thought teaches the power of mind, positive thinking, and the idea that individuals can shape their reality with positive affirmations. (Donald Trump was raised in the New-Thought-influenced church of Norman Vincent Peale, a Reformed/Methodist pastor who wrote the best-selling self-help classic, The Power of Positive Thinking [1952] – no guilt by association here, but perhaps a tip for interpreting Trump’s political art of the deal.) New Thought, in turn, has its roots in another esoteric tradition, Mesmerism, where hypnosis first emerged.

Is New Thought’s mantra – “Mind over Matter!” – an adequate solution for the problems that young people face today?

Justice and the liberal self

CAM’s guiding assumption is that students and societies face a cognitive problem that requires a cognitive solution. Three aspects of the book point to limitations of this frame.

What is the basic cause?

On the one hand, the three great untruths “are causing problems for young people.” On the other hand, a series of “explanatory threads” points to factors that “influence” people and institutions: rising political polarization, growing teen anxiety and depressing, a shift in parenting practices and university policies toward “safetyism,” loss of free play, and an increasing focus on justice. Which is the basic cause, or do these untruths and influences work together somehow? This fuzziness suggests the possibility of a deeper, underlying cause.

Procedural-cognitive justice

There is a curious resonance between CAM’s view of justice and its cognition-based framework. Many scholars distinguish between socioeconomic injustice (economic exploitation, material deprivation) and cultural injustice (nonrecognition, cultural domination, disrespect). Neither of these is the problem that CAM seeks to address. CAM rejects a “equal-outcomes” view of justice, which prioritizes uniform results over individual differences or due process. It argues for a “proportional-procedural” view of justice, which prioritizes fairness through consistent processes and outcomes proportional to individual actions or merits. The book’s vision of injustice is a world where irrationality and fragility hijack systems of judgment, leading to disproportionate responses (e.g., punishing speech as if it were physical violence) and procedural breakdowns (e.g., abandoning due process for the sake of “safety”).

This view of justice/injustice reflects the book’s premises: rational discourse is the right way to address social problems, because it assesses arguments on their merit using a fair procedure. CAM critiques campus culture for abandoning reason and being unfair, and their solution is more reason, more fairness. This is like saying, “If only everyone talked like us, we wouldn’t have these problems.” Transformative views of justice (Nancy Fraser’s, for example) can inform a more nuanced, critical theory of identity politics that the views that CAM critiques. But these are not on the table.

The liberal self

CAM’s diagnosis and prescription both presuppose a classical liberal view of the autonomous self as political agent and of reasoned discourse as the sphere where public problems get resolved.

“Liberal” means many things, in both politics and philosophy. My discussion here is narrow and points to two particular issues only. First, classical liberalism sees each person as an independent, equal, rational, responsible decision-maker; and social problems get solved when people share ideas freely, debate respectfully, and reach agreements through reasonable discussion. Second, the rise of this view was inseparable from the growth of the public sphere (from the 1500s to the 1700s) in which a growing middle class began to engage in rational debate, exchange ideas, and form opinions outside the control of traditional authorities like the church or monarchy. This also required an urban middle-class whose views developed in the more fluid middle-ground space between the contrasting rigid views of powerful elites and traditional rural communities. This shift in public discourse was a precondition for democracy, because it fostered a sense of shared agency and collective identity. The public sphere led to greater coordination of economic activities and advocacy for pro-commerce policies.

With this liberal frame presumed, CAM’s proposed solution is already implicit. The book starts and ends with a view of the university as a marketplace of ideas where rational individuals exchange and evaluate arguments on their merits, largely abstracted from power relations. CAM critiques “common-enemy identity politics” as divisive, and it defends “common-humanity identity politics,” which can develop resilience through shared human experience. If the problem is wrong thought, then the solution is right thought.

The possibility that economic and social changes are a deeper cause is ruled out of bounds. This is clearest when, as a critique of cancel culture, CAM says, “Speech is not violence. Treating it as such is an interpretive choice … that increases pain and suffering while preventing other, more effective responses….” That only makes sense if we accept the book’s starting point. Both identarian progressives and traditional Marxists would call this view a typically liberal interpretive choice. They would insist that speech actually is violence, often systemic violence, and that ignoring the fact causes pain and suffering and prevents effective responses.

What are the implications of Lukianoff and Haidt’s particular interpretive choice? They draw an implicit distinction between real violence, which is just plain harmful, and challenging discourse, which can sting if you are not used to it, but which is individually good and socially useful, because it develops resilience. This view is embedded in their initial assumptions: speech is not violence because free speech is one of the pillars of productive political culture.

Lukianoff and Haidt’s ideological frame leads them to skirt past the possibility that the problems they discuss have deeper causes. There are other views along these lines than the few they acknowledge in passing. It is possible to look at such structural issues without adopting the narrow views of left-or right-identity politics that they critique.

Beyond cognitive coddling

Other issues appear when we push past CAM’s limited focus on cognitive and discursive issues. The points below suggest that one particular structural factor deserves more discussion: global pressures from changing economic realities.

International context

Young people around the world share the pressures of soaring prices, affordable housing and lack of well-paying full-time work. Japan’s Satori generation and South Korea’s Sampo (3-sacrifice) or N-Po generation are striking examples: tens of millions of young people have given up on relationships, marriage, children, and home ownership, while experiencing rising anxiety and depression. They manifest many similar symptoms to those discussed in CAM, but that book’s three great untruths and six explanatory threads are far less prominent in those societies (in part due to more resistant traditional social relationships, reflecting Confucian ideas, though these are eroding under pressure). The impact of macro-economic issues on young people around the world deserves more attention.

Class-critique

CAM says little about social class, which seems a glaring omission given its critique of contemporary campus culture and identity politics. It takes aim at Herbert Marcuse’s skepticism about tolerance and free speech, dismissing his view that social inequalities make such ideals illusory. It also criticizes the divisiveness of some views of intersectionality (a framework that emphasizes various dimensions of individual identity, like race, gender, sexuality and disability).

CAM does not discuss a critical counterpoint: identity politics, as often practised, has drifted from its radical roots by downplaying economic class, a factor that historically binds different groups into a shared struggle. Whether you buy into a Marxist framework or not, class offers a sturdier foundation for social solidarity than a patchwork of identity silos, each vying for recognition in isolation. Intersectional theory is most effective when it weaves these threads together. To put it another way, the bread of intersectional theory rises better when class acts as the gluten in its dough, giving it the elasticity and coherence to hold identities together.

On the flip side, CAM does not consider the possibility that class could strengthen its own agenda. Its hopes for common-humanity identity politics are bound to fail if the proposed “common identity” is their own liberal view of self and society. Class critique could bridge to the views that CAM argues against, both progressive left and conservative right, without requiring this excessive ante to get in the game.

“Class” does not require full-on Marxism. It can be defined more broadly as solidarity in the light of shared oppressive economic conditions. It is enough to recognize the negative impact of global economic forces on the majority of people around the world. This perspective could yield a deeper explanation of what causes the problems that young people face today. It also calls for a very different discussion of solutions. Even a binary class perspective, global elites versus the rest of us, would offer a basis for effective critique and solidarity.

Part of the problem?

If the globalization of the economy is the deeper problem – if it has undermined meaningful options for younger generations – then CAM’s perspective is not just misdirected, it props up the system. Telling individuals and universities to foster resilience presupposes that they can still have a meaningful impact on their material conditions. Clear thinking is not enough if liberal agency has no power anymore, if self-help is its only outlet. If that is the case, then defending outdated views of the university and teaching cognitive behavioural therapy is beside the point. If the old marketplace of ideas is no longer an arena for shaping social and economic realities, then universities and scholars need to get real about the new marketplace. We should be talking less about how we talk and more about relations between the monetization of information, macro-economic structures, and global policy convergence.

The economic shaping of the self

The seemingly autonomous liberal self that CAM presupposes was shaped by economic transformations over many centuries. The emergence of a public sphere took place in cities, where traditional community and extended family relationships were already weakened. Processes of individualization have continued. Max Weber and Émile Durkheim argued that the drive for rational efficiency and skills specialization eroded traditional social bonds, shaping people into atomized individuals, more suited to a modern economy. This was accelerated by further urbanization, industrial labour markets, and extended educational requirements. On this view, the liberal self was not a triumph of human progress: it was a product of and fodder for economic systems.

Current economic developments have gone beyond eroding tradition, community and the family. They are fragmenting the self, splitting the atomized individual into constituent particles. Work has always required only some of our capacities: assembly line workers and construction labourers have little need for abstract thinking; accountants and university professors are not hired to lift heavy things. None of us are ever paid for just being ourselves, whole, complete, and unified.

But we are moving into new territory. Young people especially are experiencing the monetization of fragments of the self: attention, clicks, algorithmic engagement, gamification, personal data valuation, and micro-performances of identity. Digital platforms are transforming human experience into a series of quantifiable units—every interaction and decision and is a commodity to be measured, traded, and optimized. This is a qualitative shift in commodification, from broad labour capacity to micro-experiences. The mind is being parsed for its components’ value. Attention, above all, is a prized commodity. CAM is right that young people face a cognitive threat, but perhaps the problem is not the erosion of liberal, Enlightenment reason. Perhaps it is the fact that cognitive patterns, attention mechanisms, and emotional responses now have price tags. Digital platforms have intensified a long-standing process of commodifying human capacities, but now with unprecedented granularity and reach.

This extends the idea of what Marxists call “alienation.” Where industrial capitalism alienated workers from the results of their own productive work – which was sold for someone else’s profit – digital platforms alienate people from their own lived experience, not just at work but in every moment of their leisure time. The monetization of fragments of self is a more total form of alienation - not just estrangement from labour, but from one’s own subjectivity. Byung Chul Han, in Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and Technologies of Power, argues that technological developments are “entangling us in exploitation along new lines”:

Now, immaterial and non-physical forms of production are what determine the course of capitalism. … The body no longer represents a central force of production, as it formerly did in biopolitical, disciplinary society. Now, productivity is not to be enhanced by overcoming physical resistance so much as by optimizing psychic or mental processes. Physical discipline has given way to mental optimization.

Optimization for profit, not for a better lives and better societies.

Welcome to the informational gig economy

If this is true, then perhaps young people’s “problems” reflect these economic and societal changes more than their own fragile thinking. Could there be an upside, a way to put at least some positive spin on this blood-curdling prospect? The wired, media-mired, technology-embedded, anxious selves that Lukianoff and Haidt lament are a product of our times. Young people’s fragmented, modular, monetized minds are adapted to this new reality, because they were shaped by it. In that light, perhaps young people’s anxiety is the price they pay for being better prepared for the future.

Historically, the nexus that formed the liberal self brought significant costs – poverty and harsh working conditions for many, along with the erosion of tradition, local communities and extended families – but it had certain benefits. The same can be said of iGen and the Satori and N-Po generations: many young people are paying a high cost of mental stress and economic marginalization; but many are simply shaped by – and so better suited to – these strange times. They have developed technological fluency, information processing skills, adaptability to fragmented work environments, and a capacity to navigate complex, rapidly changing economic landscapes. They are made for (because shaped by) a radically different economic system.

Perhaps the most important truth is that most young people today are better prepared for new economic and social realities, far more than older university professors who watch from the side-lines and recommend cognitive therapy as a fix for their students’ “problems.”

Conclusion

“To curdle” is to separate solid parts out of a liquid: curds and whey, blood clots and serum. First we curdle the milk, then we fish out the valuable parts, so we can profit from making cheese. Over the past two decades, aspects of human cognition have been separated out and monetized. This granular extraction of cognitive and emotional capacities is unprecedented: it is the curdling of the global mind. Where previous economic systems fragmented individuals through work specialization and urban displacement, digital platforms now break down the self into quantifiable, tradeable units. People reach for their cell phones in all their idle moments: in the bathroom, waiting for an elevator, waking at night, during meals with friends, in transit and meetings, while “watching” other screens... The always eager roots of capitalism have breached the walls of private leisure time and infiltrated individual minds in new ways.

The Coddling of the American Mind is limited by its self-help paradigm. It frames systemic economic pressures as personal psychological failures, and it wants to reboot an outdated view of the university as arena and champion of public discourse. This ignores the current economic reconfiguration of human experience. If cognitive fragmentation is a systemic effect of digital capitalism, then “resilience” risks being not a solution but another technology of economic optimization. I see potential for an anti-fragility app.

The university is not a sanctuary from economic pressures, but a place where they are echoed and reproduced. Addressing the psychological toll of contemporary capitalism requires re-imagining institutional spaces – not as cognitive therapy clinics, but as potential grounds for collective resistance to the curdling of human minds.

Or you can just swipe left on this post.

[Thanks to my long-time colleague, philosopher Sinclair Macrae, for organizing a reading group on CAM, which got me thinking more than usual about these issues.]

It’s refreshing to see a pushback against the rhetoric of resilience being used to delegitimize expressions of care, protest, and vulnerability. The real issue is not oversensitivity, but exhaustion, disillusionment, and a justified sense that the game is rigged.

A lot of truth here.